Every so often someone will ask me what I think about the latest problems in American society. I often refrain from comment on the simple grounds that I am overqualified for the task. “After all,” I say, “it doesn’t take a PhD in critical theory to figure out what’s wrong with the United States.” Since I literally have a PhD in critical theory, finding fault with the U.S. is like shooting a fish in a barrel. The answer to every problem is obvious: too many guns, archaic constitution, majoritarian voting system, distrust of government, too many veto points, etc.

This isn’t really what I believe, it’s just something I say to escape from conversations that I’ve had too many times. My actual view is that critical theory is much harder and more challenging in the U.S. than in practically any other Western country. This is due to a pattern that appears in almost every case: For every obvious problem in America, there is an obvious solution. And yet for every obvious solution, there is a somewhat-less-obvious problem, which blocks the implementation of that solution. That less-obvious problem also has a solution, but there will usually be some significantly less obvious problem, which blocks implementation of that solution, and so on.

The challenge therefore in U.S. critical theory – that which does require a PhD to puzzle out – is to trace back this escalating hierarchy of problems, in order to understand why, as a general rule, nothing in America ever gets fixed. (At best, Americans figure out a way to work around their problems. This generates an accumulation of complexity, opacity, and inefficiency over time that is distinctive of American government, which some have referred to as “kludgeocracy.” This also cannot be fixed.) Unfortunately, almost no critical theorists have the level of patience for institutional detail required to engage in this “trace back the problem” exercise.

Naïve critical theory, in a U.S. context, consists of pointing at an obvious problem and saying “OMG someone should stop this!” (or more often “we could fix this, if it weren’t for those dastardly Republicans”). Mid-level critical theory is achieved when commentators begin to wonder why, despite the fact that everyone has been talking about how something is a problem for decades and decades, nothing ever seems to get done about it. Big-brain critical theory is achieved when commentators begin to realize that every major problem in American society can be traced back to commitments that are broadly shared in the population, by both Democrats and Republicans.

I came across a good example of this the other day when thinking about the problem of housing affordability, which is a major issue in both Canada and the U.S. An important difference between the two countries, however, is that in Canada the problem has generated something that at least vaguely resembles a rational policy response. Most importantly, it has led governments at all levels to focus on building more housing. Anyone who has tried to drive anywhere in Toronto in the past few years will have noticed that these efforts are producing results. There’s a lot of construction going on!

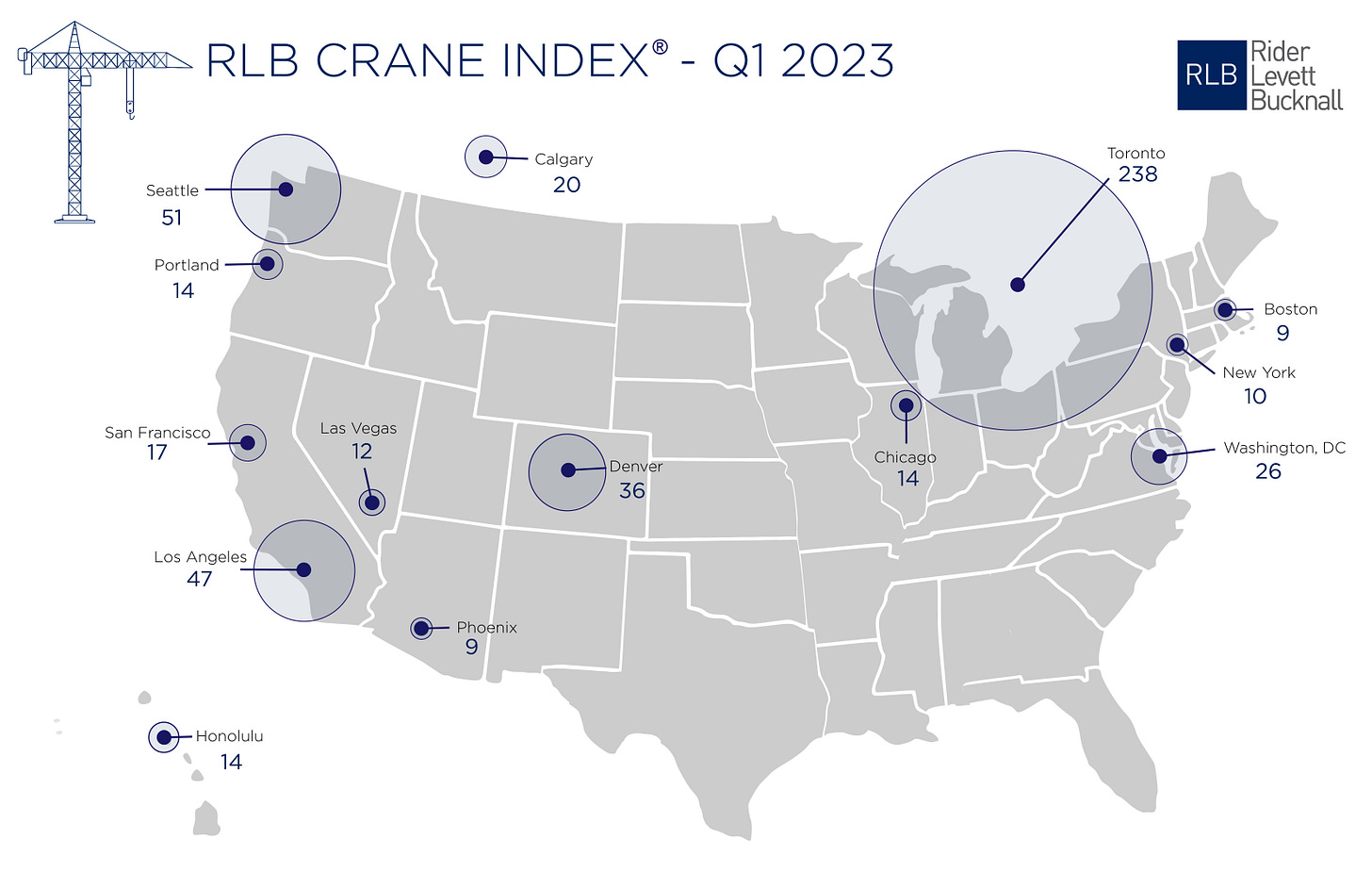

I was struck by the following handy infographic, which shows the number of fixed construction cranes in various major cities in North America at the beginning of last year:

Some quick math shows that Toronto and Calgary have more construction cranes than all of the listed U.S. cities combined (including New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago and Boston!). What is mind-boggling about this statistic is not all the construction that is going on in Toronto, but all of the construction that is not going on in New York and San Francisco. (Also, just to be clear, almost all of those cranes in Toronto are doing residential construction. The commercial property market is glutted, having not yet recovered from COVID.)

I feel somewhat guilty listening to the YIMBYs in the U.S., like Matt Yglesias and Ezra Klein, fighting the good fight on this issue. The level of knee-jerk opposition to urban density they have to contend with is truly impressive. (I may be naïve, but I was surprised at how much resistance the residents of SoHo and NoHo in New York City gave to an “upzoning” plan to permit taller buildings and more residential construction in those districts. Just to be clear, these are people who live on the island of Manhattan, fighting tooth and nail against the construction of tall buildings in their neighbourhood. If they really hate urban density that much, you have to wonder why they don’t consider living... let’s see… literally anywhere else in America.)

So how has Toronto managed to overcome this sort of opposition, in order to get stuff built? This is where the comparison between the two countries becomes more interesting. The answer is: through executive power. More specifically: by taking power away from both elected officials and judges and putting it in the hands of bureaucrats. Even more specifically: the Province of Ontario has radically reduced the number of veto points in the construction approval process by creating an administrative tribunal with the power to make binding land use decisions. This tribunal has the power to override city council bodies, and is protected from judicial review through a privative clause.

In its current incarnation, this tribunal is known as the Ontario Land Tribunal. (Those of a wonkier inclination might be interested in checking out the enabling legislation here, paying particular attention to the privative clauses – which limit judicial review of tribunal decisions – in sections 13 and 24.) It would be difficult to overstate how entirely foreign this institution is to American political tradition, on multiple levels. The whole thing has “unconstitutional” written all over it.

I got to see the operations of this tribunal a few years ago, in my neighbourhood in downtown Toronto (the tribunal was known at the time as the Ontario Municipal Board, or OMB). I lived in a leafy residential neighbourhood, full of detached single-family houses, about a five minute walk from the St. Clair West subway station (which is to say, very close to the city centre). One day a neighbour knocked on my door, asking me to sign a petition. There was, on my street, one slightly larger building, which occupied two regular lots and contained six living units. The owner had wanted to rebuild it, increasing the number of units to 24.

Naturally everyone in the neighbourhood was opposed, hence the petition. To my credit, I refused to sign it, although I should note that the level of fortitude that it took to do this was non-negligible. There’s a lot of peer pressure when your neighour is standing at your doorstep, asking you to contribute to the community project. The cost of signing is basically zero, while the cost of refusing is both the awkwardness of the immediate interaction and the potential long-term cost of annoying your neighbours (e.g. neighbours that you hope will look the other way when you do some small renovations to your house without the appropriate permits).

As is often the case in older cities, every house in my neighbourhood was in violation of various construction and land-use bylaws. If you just leave your house the way it is, these violations make no difference. But if you try to renovate anything that requires a permit, it means that your proposed renovation will almost certainly violate the bylaws (e.g. if your entire house is built too close to the property line, violating set-back bylaws, then any renovation that you do to your house will also violate set-back bylaws). As a result, you have to apply to Toronto city council’s Committee of Adjustment to get permission for a bylaw variance.

The Committee of Adjustment is also an administrative tribunal, but it is very close to municipal politicians – its “citizen members” are all appointed by council. Most importantly, it holds public hearings, in which “all owners of land within 60 metres of the subject property” are invited to comment on the request for a variance. So in practice it functions as a NIMBY veto point. This is where my neighbours took their petition. Predictably, they won, and so the project was blocked.

Undeterred by this setback, the owner (or developer) appealed this decision to the OMB. A month or two later a decision came back from the OMB, overruling the Committee of Adjustment and approving the project. (As local residents, we all got copies of this ruling in the mail.) I recall having been surprised at how terse their explanation was. It basically said “This building is situated within walking distance of a subway station. City plan licenses increased density near transit. Project is approved.”

Okay, so this is just one little story, about one little piece of the planning bureaucracy in Ontario. A complete account of how Toronto wound up with 238 construction cranes would be a great deal more complicated. Furthermore, the housing problem in Toronto is very far from being fixed. My point is simply that the problem has elicited a rational policy response, such that it is not unreasonable to expect things to improve over the next decade. By contrast, people living in San Francisco and New York have been given no reason to think that anything will ever get better.

The purpose of the story is to make a much more general point about America and why they have such difficulty solving problems. As Canadians, our first impulse is often to say “why don’t they just do it the way we do here?” The answer is usually that it is impossible to do things that way in the U.S. In the case of housing, you can’t just create administrative tribunals to overrule local councilors. You also can’t sprinkle privative clauses into legislation to prevent judicial review. And you usually can’t confer that level of discretionary judgment on public officials.

Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, neither liberals nor conservatives in the U.S. are willing to make the changes that would be required to make it possible to do any of these things. This is why so many superficial problems in American society turn out, on closer inspection, to be deep problems. It’s not that Americans can’t make the right decisions, its that they are not willing to create the governance structures that will allow people to make the right decisions, or to carry them out once made.

So what does a critical theory of (or for) America look like? Most importantly, it looks a lot more institutional than a critical theory developed for any other Western nation. Nothing annoys me more than listening to American leftists fantasizing about socialism, when they have a government that can’t even implement the metric system. This is a massive blind spot in American political thinking. But again, if you bring up lack of state capacity and the overall poor quality of U.S. public administration, both liberals and conservatives will immediately propose changes that will demonstrably make things worse – essentially doubling down on the demands that have created the current unsatisfactory state of affairs. These are the hard problems in American public life; the ones that serious critical thinkers focus their attention on.