I have an old friend who is a drama queen. I don’t mean this in the stereotypical sense, that she goes around screaming and yelling at people. She’s an educated, intelligent woman, as a result of which her behaviour is quite subtle. So subtle, in fact, that it took me years to figure out what was going on with her.

In her life, she occupies a central position in a complex web of interpersonal relationships. These relationships are never fully stable, there is always something “going on,” always some sort of a problem that she is eager to discuss. It is very easy to get drawn into this. For the first decade or so that I knew her, whenever she would tell me about these problems, I would listen attentively, consider the various angles and perspectives, and then suggest some possible solutions.

Over time, I began to notice that these suggestions were never acted upon. In fact, the interpersonal problems didn’t ever really get solved, more often a new set of problems would come along, which were in some sense more interesting and important, and so her attention would shift over to them. Furthermore, if she did happen to solve one problem, another one would always appear, seemingly out of nowhere, to take its place.

For a long time this puzzled me, until one day the truth dawned, with the full force of its blinding self-evidence. She wasn’t really interested in solving the problems, or even in the problems themselves; it was the drama that interested her. It gave her something to talk about, something to think about. It was entertainment, it was stimulating. Because of this, even though the drama was in one sense quite real, it was also being manufactured to serve her own psychological needs.

This realization led to something of a decline in the closeness of our friendship, as I found it increasingly difficult to summon as much interest in her problems. (My own approach to interpersonal drama is quite the opposite of hers, in that my first impulse is usually to ignore it for a month or two and see if it goes away.) In retrospect, my attitude was quite naive. I simply assumed that, since problems are bad, sensible people should want to solve them. More specifically, I assumed that conflict is bad, and so people should seek avoid it when possible and resolve it when it occurs.

At some level, of course, I knew that this was not true. Reality television producers have become somewhat infamous for going out of their way to provoke conflict among participants in their shows. That’s because reality is boring. Conflict, on the other hand, is interesting. It grabs our attention. It is stimulating. Fiction writers know this, which is why they focus relentlessly on conflict. Reality does not deliver it quite so reliably, which is why the people who stage reality television shows often find themselves having to instigate it.

It took me a while to put two and two together on this – to realize that just as people might seek to provoke conflict on a reality television show, in order to make it more interesting, people might also seek to provoke conflict in real life, in order to make it more interesting. My obtuseness in this regard is compounded by the fact that I share, to at least some degree, the Canadian trait of being highly averse to conflict.

People who are familiar with my written work might find this claim either surprising or unbelievable, given that my public interventions have been, on occasion, controversial. The difference, however, is that I derive no pleasure from arguing with people. That’s why the comments are turned off below. I write the way I do because I think I’m right, and I would like others to see things my way, but I have absolutely no interest in fighting about it.

By contrast, when I listen to someone like Jordan Peterson what I am struck by most forcefully is his seemingly insatiable appetite for conflict. To be honest, I get irritated by many of the same things that he finds irritating – working in a university these days involves not just being bombarded with bullshit, but being surrounded by people whose bullshit-detectors appear to be in a state of complete malfunction. At the same time, I derive no pleasure from picking fights with my colleagues. (My impulse, like that of most sensible academics, is to ignore it all for a few years and see if it goes away.) The eagerness with which Peterson kicks one hornet’s nest after the other is something that I find, not just foreign to my emotional sensibility, but incompatible with my most basic vision of the good life.

This observation, unfortunately, runs somewhat contrary to my claim that conflict-aversion is a Canadian trait. I’m inclined to treat Peterson as more the exception than the rule. Maybe it’s because he’s from Alberta and I’m from Saskatchewan. Or maybe it’s because Canadians who enjoy picking fights wind up moving to the U.S. Because if there’s one thing that can be said about Americans – although again, this took me an embarrassingly long time to figure out – it’s that they enjoy conflict.

Allow me to preface this by noting that the most common mistake Canadians make, when thinking about the U.S., is to imagine that we understand the place. Living there for a few years was enough to cure me of this delusion. America is a vast, sprawling, fragmented, deeply mysterious nation. The most important thing that I learned, living in America, is that I do not understand America, and probably never will. As Canadians we are, in a sense, almost handicapped in our efforts to understand America, because of the superficial similarities between our two countries, which generates a false sense of familiarity.

In any case, one of the things that has always puzzled me about Americans is that they are always so extreme. Everything they do is over-the-top. Part of the reason they have so many checks and balances in their political system is because people are so uncompromising. (It’s not clear which came first, the institutions or the immoderation.) This is true of Americans generally, regardless of their politics. For example, there was about a one-week period, after the death of George Floyd, in which sensible people said some sensible things about how policing in America could be improved, until they were completely drowned out by demands to “defund the police.” Similarly, just when the discussion about reducing mass incarceration in the U.S. was becoming serious, American academics decided that this would be a great time to relitigate the case for prison abolition.

While the media is full of examples of over-the-top behaviour among American conservatives enthusiastic about “owning the libs,” it is important to recognize that American liberals/progressives are also constantly, constantly provoking conservatives in completely unnecessary ways. (For example, it was not enough for Harvard University to use affirmative action to eliminate racial disparities in admissions. They had to proudly announce, in the very year that their policies were being challenged before the Supreme Court, that blacks were overrepresented in their student population.) A lot of the success of the “defund the police” slogan was due to the simple fact that it clearly and visible upset the leaders of police departments – many of whom hastily called news conferences to defend their budgets. Even if the demand was insane — as though America could be transformed into a well-ordered society through a modest reallocation of funds to social services — people found the reaction that it provoked quite gratifying.

The difference is that when the left is being unnecessarily provocative, they often have a high-minded moral rationale for their behaviour. Because of this, I spent a long time naively trying to figure out why so many Americans always seemed to feel morally obliged to take the most extreme position possible. Similarly, I was puzzled by how they could spend so much of their lives criticizing various problems in their society, and yet exhibit so little interest in solving any of these problems, or even articulating what a solution would look like. It simply hadn’t occurred to me that they might enjoy fighting over these questions – that the conflict might give meaning to their lives, or at least offer distraction from the everyday.

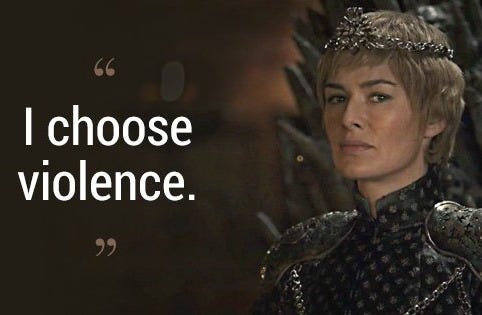

In recent years, I have begun to think of Americans as the drama queens of the Western world. In the recent election, given a choice between boring, business-as-usual politics, and dramatic, polarizing politics, they clearly chose drama (whether they also chose violence remains to be seen). The most revealing moment in the campaign, for me, came just after the first attempted assassination of Donald Trump, when he rose from the ground, still somewhat disoriented, and yelled “fight, fight, fight!” (prompting Logan Paul to describe the scene as “the most badass thing I’ve ever seen in my life”). What I remember, on the other hand, was thinking to myself, “fight for what?” This was, of course, to miss the point, in a typically Canadian way – to imagine that fighting must have some external goal or purpose. The idea that it could be an end in itself, a source of direct gratification, is not one that came naturally to me. So again, it took me a while to see that Trump’s fist-pumping exhortation to fight had no external objective or referent. It was a perfectly self-contained statement of what he was offering the American people: “fight, fight, fight!”