Canadians should think of higher education as an export industry

I need everyone to bear with me for a moment, because what I’m about to say makes perfect sense, but it sounds funny when you first hear it. In the short term, the influx of foreign students into our higher education system is creating all sorts of hardship for Canadians. This has led the government to intervene (in my view appropriately), in order to restore some semblance of order to the file. At the same time, it is important to ask ourselves – beyond the short-term objective of restoring order – what the long-term goal of policy in this area should be (so that we can, as the Great One put it, skate to where the puck will be).

Thesis statement: In the long term, our goal should be to sell higher education to as many foreign students as we feasibly can. Why? Because it is a high value-added export sector. Specializing in this area is a great way to move the Canadian economy away from our traditional role as “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” and to avoid the pitfalls of economic globalization. Universities generate a huge amount of high-quality white-collar employment, as well as creating opportunities for regional development that are otherwise difficult to achieve.

Let me back up and explain a few things. First, most people do not think of international student enrollment at the University of British Columbia or George Brown College as an export product, because the goods don’t actually leave the country. But of course, from an economic perspective it doesn’t matter whether we move the goods to the foreigners or the foreigners to the goods. What matters is that, by selling things that are made in Canada, by Canadian workers, to foreigners, we earn foreign currency. This foreign currency is what then allows us to go out and buy things that are made by foreign workers.

To get the overall picture, it is worth taking a stroll through an Apple Store (at the high end) or a Dollar Store (at the low end), keeping in mind that absolutely none of this stuff is made in Canada, it is 100% imported. Then ask yourself “how do we pay for all this?” The non-economist’s answer is to say “with money.” That’s incorrect, because although you can pay for your dollar store purchases with Canadian money, the Chinese manufacturers who actually make the merchandise have to be paid in Chinese renminbi, and so somewhere in the chain that flows from your payment at the cash register to the reimbursement of the person who made the goods, money must be converted from Canadian dollars to Chinese renminbi. This means that some foreigner has to be willing to buy Canadian dollars.

The important thing to realize about Canadian dollars is that while they’re very useful to those of us who live in this country (because we can use them to pay for groceries, entertainment, our taxes, etc.), they are significantly less useful to foreigners (who cannot use them to pay for their groceries, entertainment, taxes, etc.) They can only be used to buy Canadian goods (or other currencies, but ignore that since it just pushes the problem back one step). This is why Canada, like every country, needs an export sector – we need goods that we can sell to foreigners. Exports are how we pay for imports.

Ideally, what you want is to have some sectors in which Canadians are much better at producing things than foreigners are, relatively speaking, so we can make a lot of the stuff that we’re good at producing, to sell it abroad, and then stop making the stuff that we’re bad at producing, and import it instead. So when you think about Canada’s place in the global economy, you need to look at the country as a whole and think “what are we really good at making?” And in order to think strategically about it, you need to look at the future, at the direction of the global economy, and think “what could we be really good at making?”

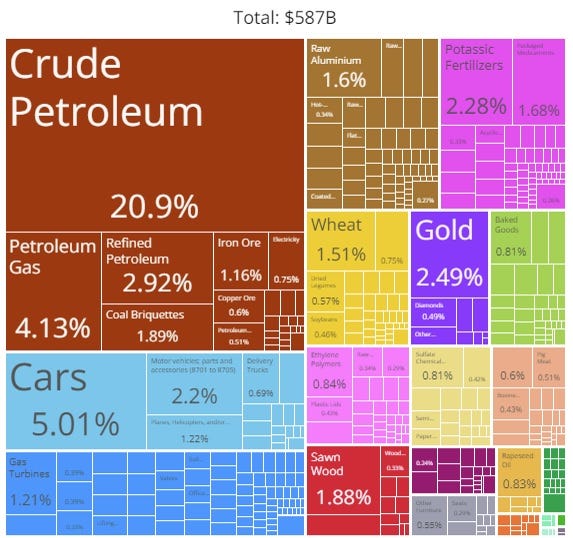

Taking a quick look at the current profile of Canadian exports, it’s not difficult to spot the problem (although if you follow the link and scroll down a bit you can find “service trade” which is not quite as disconcerting):

There’s a reason that the Canadian dollar is considered a “petrocurrency.” A lot of people (myself included) would like to see that “crude petroleum” box become a lot smaller. To which a critic might reasonably respond, “okay smart guy, if it’s not going to be petroleum, then what else are Canadians going to produce, to sell to foreigners?” Anyone who worries about climate change should spend at least a bit of time thinking about this question.

Part of the answer could be education. What if we were the country that everyone in the world wanted to send their children to for a high-status post-secondary education? Would that not be a great niche to occupy in the global economy? This is something that the U.K. figured out a while back. The French have a lock on the global luxury handbag market. So the British decided to get a lock on the global luxury education market – leverage the Hogwarts fantasy, along with the generally high quality of British schooling, into comparative advantage in higher education.

Canada unfortunately does not have the cultural capital that the U.K. enjoys. What we do have, however, is significant experience at preserving quality while exploiting scale economies in higher education (something that upper-end British and the American universities are terrible at). My back-of-the-envelope calculation says that the University of Toronto took in $1.5 billion from foreign student fees this past academic year. That’s not enough to register on the chart above, but at the same time, it’s not chump change, and that’s just one university.

Canada has one other significant advantage in this sector, which arises as a consequence of domestic multiculturalism. Foreign students who come to North American universities sometimes complain about social isolation, a problem that, somewhat paradoxically, winds up getting worse as the number of foreign students increases. In particular, if there are too many students from China, they may find it easier just to socialize with one another, because it’s less awkward than trying to make small talk in English. As the number of foreign students increases, this self-isolation becomes more viable, which in turn deprives these students of the Western university experience they are looking for. In Canada, however, first and second generation immigrant students act as a social solvent, especially when they are fluently bilingual, so we get much better integration among students.

That’s how things look from a long-term, strategic perspective. The current situation is obviously very far from the ideal, in part because much of what we have been selling to foreigners, in the higher education sector, is not actually the education, but rather a Canadian work visa and path to Canadian citizenship. This was, I suspect, an unexpected consequence of an otherwise reasonable policy, which was to stop kicking students out of the country the day after they graduate. But things obviously got out of hand, in part because of poor coordination between the provinces (who run education) and the federal government (which runs immigration). This needs to be fixed, so that what we’re selling is just the education.

I should mention as well that the idea of charging foreigners top dollar for a Canadian university education (at UofT we charge international students $61,720 per year for a basic Arts program, versus $6,910 for Canadians) rubs some people the wrong way politically, because they think that the low rate for Canadians is due to there being something objectionable about the principle of market pricing for higher education. This can be taken to imply that non-Canadians should pay low rates as well. I think it makes more sense to see the subsidy paid by Canadian taxpayers to university students as a way of achieving certain goals in Canadian society (such as increased social mobility), which does not justify subsidizing foreign students. Foreign states trying to achieve similar goals in their own societies are free to subsidize their own students, as China often does, but there is no reason for us to be subsidizing them.

One final point, which is that the education file has intersected with the housing file in a really unfortunate way. A lot of colleges, and some universities, have brought in thousands of students without thinking too hard, or taking much responsibility, for the effects this will have on the local rental market. Housing supply is, of course, elastic in the long run – assuming we get development and zoning policy right – and so again this is more an issue of medium-term adjustment. The only observation I would make is that, with all the clamping down on foreign buyers in the Canadian housing market, it is important to keep in mind that housing can also be an export. If we can make millions of dollars selling overpriced condos or suburban homes to foreigners (or if universities can charge foreign students to live in residence), that’s also a great way to earn foreign currency. We just have to get the policy right, so that catering to the export market does not price out or displace younger Canadians trying to enter the housing market.