Combatting extremism

There is a natural temptation to believe that people who perform extraordinarily antisocial acts must possess some extraordinary motive for doing so. This turns out to be untrue. One of the earliest discoveries of criminologists was that most people who do very bad things are not fundamentally different from the general population. Their motives are usually familiar to us, it’s just that they experience them more intensely (or fail to inhibit them as completely).

Similarly, one of Sigmund Freud’s major contributions was to have observed that what we call “mental illness” often involves just a more extreme version of psychological weaknesses that we all share (or, again, a failure of inhibition with respect to those weaknesses). In The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, he aimed to show that while these tendencies are debilitating for some people, they can be found in less extreme (and thus non-pathological) form in the rest of us. The lesson to be learned is that we’re all crazy, just some of us more so than others.

Because of this, when we think about extremism, our focus should be on the distribution of certain traits (understood broadly) in the population. It is wishful thinking to believe that extremists subscribe to some distinctive “extremist ideology” that we could target for eradication. They seldom do. For the most part they have the same stupid ideas as the rest of us, only more so.

Unfortunately, people are not very good at thinking about distributions, because we tend to focus on the average (or mean), whereas often what we should be focusing on are the outlying ends of the distribution. (Malcolm Gladwell wrote a good article on this point a long time ago.) And when thinking about outliers, the variance within the distribution is often just as important, if not more important, than the mean. Yet we often ignore this. Indeed, the average educated person has some knowledge of what the average values are for many economic and social statistics, but no idea how much variance there is.

All of this becomes quite important when we turn our attention to extremism, because extremists are, almost by definition, outliers. The best way to combat extremism is of course to adopt policies that specifically target extremists, either to reform or deter them. But precisely because of this, extremists often conceal their extremism from others. As a result, most policies aimed at combatting extremism must be formulated under conditions of severe information asymmetry, which means that they have to be targetted at the population much more broadly. This can have some counterintuitive effects.

I presented a very simple example of this a few weeks ago, at the paper I gave in Montreal about combatting racism. Since the slides in question are not in the written paper, I thought I might reproduce them here. The trait that I was interested in was intolerance (although one could apply the same analysis to a variety of other traits, such as alienation), which I took for the sake of argument to be normally distributed in the population. Most people succeed in suppressing whatever intolerant attitudes and thoughts they may have, and so it is only at the far right-hand end of the distribution that it manifests itself in the form of overt racism. So the major objective of anti-racism policy is to make these “problem cases” disappear.

Assume also for the sake of argument that people are good a concealing intolerance, so whatever policies are adopted will have to be applied to the entire population. The only solution, in other words, is to change the distribution. There are, however, two clearly different approaches that one could take to this.

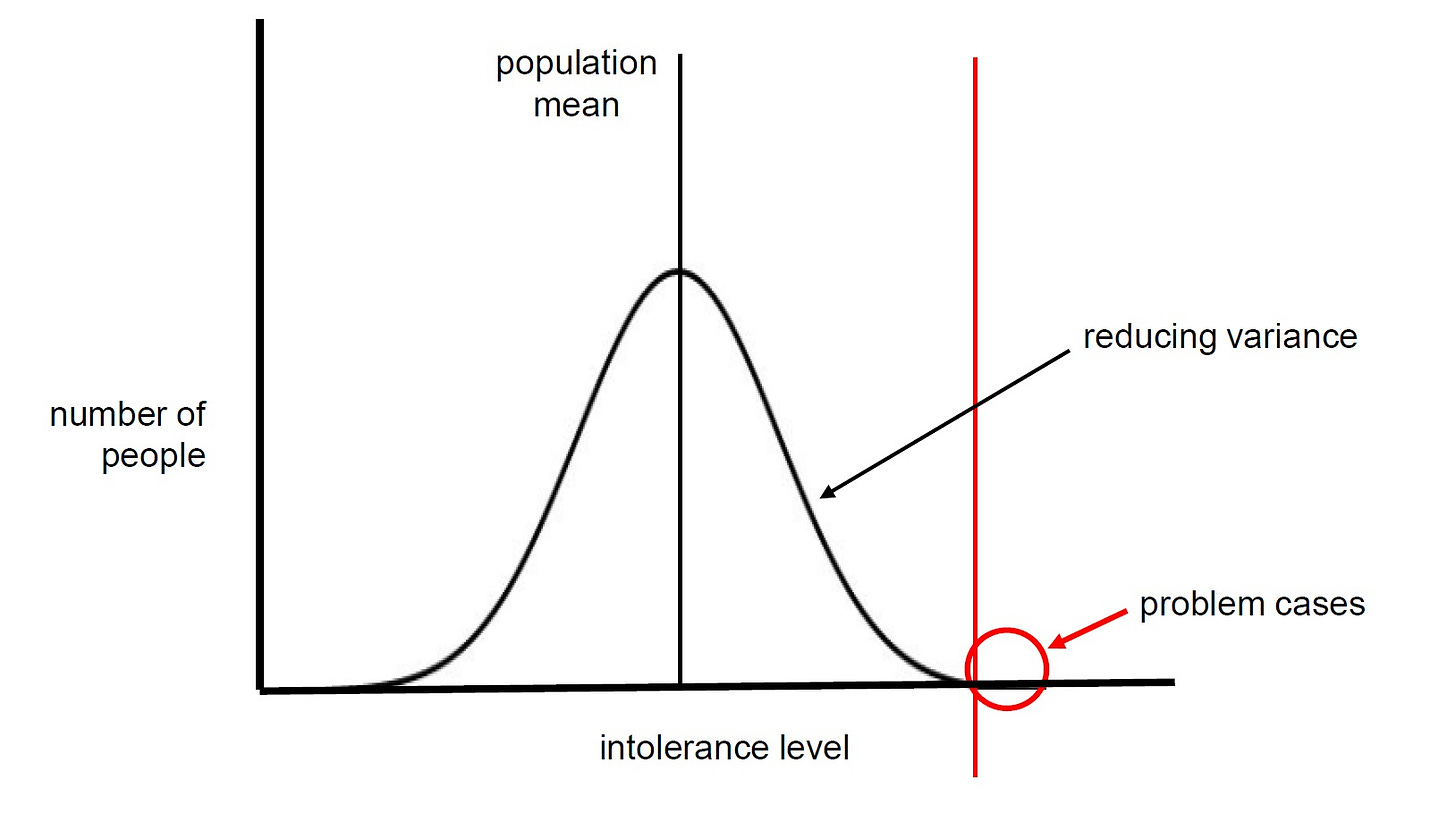

The first strategy, shown below, would be adopt policies aimed at reducing the variance of the trait in the population. (An example of such a policy would be one that encouraged greater conformity to mainstream sentiment.) This strategy would leave the average level of intolerance unchanged; it would eliminate the problem cases by getting the population to cluster more closely around the mean.

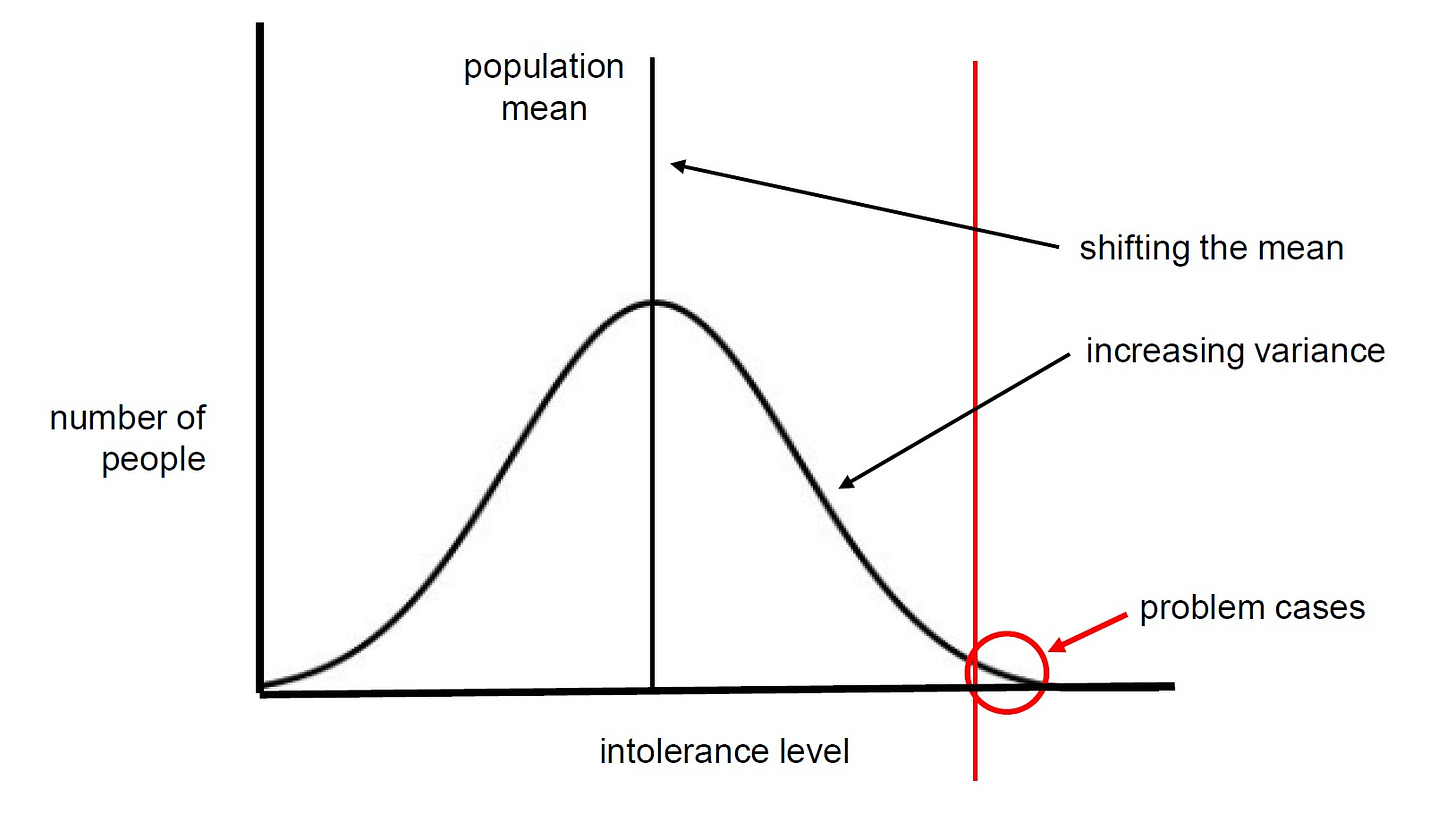

The second strategy would be to adopt polices aimed a shifting the entire population mean to the left. This does nothing to reduce the number of people with outlying views, it just brings them under the threshold of socially acceptable behaviour.

People tend to prefer this second strategy, because it can plausibly be described as moving toward eradication, while the first seems more accommodationist. It is, however, possible for a perverse effect to arise, if the policy aimed at shifting the mean also has the effect of increasing the variance in the population. In this case, one can have a seemingly-paradoxical situation in which the average level of intolerance is dropping, and yet the number of problem cases is increasing! (see below)

This is extremely schematic, but I think it provides a good model for thinking about what has been going on with anti-racism efforts over the past decade or two. Public opinion surveys all show a steady decline in intolerance, and yet it feels as though there is greater prevalence of overtly racist speech. Some of this, of course, is simply an effect of the loss of media gatekeepers and a decrease in social viscosity, which forces us all to listen to people that we would previously have had no occasion to interact with. And yet there is also reason to think that social media has increased variance with respect to many antisocial traits. The internet has, in effect, potentiated social deviance, by making it so much easier for individuals with outlying views or preferences to find one another and offer mutual support. I think the increased prevalence of conspiracy theories, for example, is largely explained by this mechanism.

The more interesting question is whether our efforts to shift the entire population to the left with respect to racial tolerance could itself be contributing to an increase in variance. This strikes me as one way of thinking about “backlash” phenomena. Certain efforts on the anti-racism front, for example, have been polarizing, in the sense that they seem to generate a lot of true believers and a lot of reactionary opponents (i.e. increased variance). This could create a situation in which things are improving on average, and yet the social climate is deteriorating.

All of which suggests that we should be thinking more explicitly about what our implicit models of social change are, as well as how the policies that we adopt to achieve change are targetted. We should also be prepared to respond flexibly when those policies appear not to be achieving their desired effects.

______________

P.S. The Gladwell article linked to earlier takes a while to get to the interesting idea, which is his critique of our tendency to design programs that focus on the middle of a distribution rather than the problematic tail. The best part is his discussion of the post-Rodney King investigation of the LAPD, and the effort to combat what we would now call “systemic racism” on the force:

The report gives the strong impression that if you fired those forty-four cops the LAPD would suddenly become a pretty well-functioning police department. But the report also suggests that the problem is tougher than it seems, because those forty-four bad cops were so bad that the institutional mechanisms in place to get rid of bad apples clearly weren’t working. If you made the mistake of assuming that the department’s troubles fell into a normal distribution, you’d propose solutions that would raise the performance of the middle—like better training or better hiring—when the middle didn’t need help. For those hard-core few who did need help, meanwhile, the medicine that helped the middle wouldn’t be nearly strong enough