How Steve Bannon baited the American left into overplaying its hand

Although he’s not quite finished with us yet, I think it fair to say that Steve Bannon will be remembered for two things: first, his media management strategy (“flooding the zone with shit”), and second, having popularized a Breitbart slogan (“politics is downstream from culture”) that wound up becoming the opening salvo in the U.S. culture wars. The latter idea is closely tied to the claim that, in the aftermath of the 1960s, “Liberals took over Hollywood, while Conservatives took over Washington.”

My ears perked up when I first heard this argument being discussed, back in 2017, because as some may recall, Andrew Potter and I wrote an entire book (The Rebel Sell, 2004) making the same observation, but drawing the opposite political lesson. We claimed that progressives had become obsessed with cultural politics, but that in so doing had made the wrong choice, because politics is not actually downstream from culture. Focusing on obtaining political power – the way that, for example, evangelical Christians in the U.S. had been doing – would have been the better move, we argued. Bannon was now claiming the exact opposite – that conservatives had made a huge tactical error in focusing on obtaining political power while ceding control of cultural production to liberals.

As the late Andrew Breitbart put it, “The left is smart enough to understand that the way to change a political system is through its cultural systems.” He attributed this view, not incorrectly, to the first generation of Frankfurt School theorists, who had argued that the emergence of bureaucratic management, first and foremost in the welfare state, provided a technocratic solution to the crisis tendencies of capitalism, and so the lynchpin of the system had become the “culture industries,” which served to inculcate the ideological convictions necessary for the reproduction of the entire social order.

This idea, that culture is some all-powerful, controlling force, tantamount to a system of mind control, proved enormously attractive to many people. It has been difficult to dislodge, in part because it flatters the self-conception of so academics and journalists. English literature professors are haunted by the suspicion that the books they teach are just high-brow entertainment, and so love nothing more than being told that their interpretive methods are sounding the death-knell of Western civilization. And of course people who work in the entertainment industry are happy to think that they are not just in the business of providing entertainment, but are instead at the cutting edge of the struggle for social justice, reprogramming the software of the human mind to promote greater tolerance and equality. It’s all very empowering, even when formulated as criticism.

One might think that the events of the past few years, especially the U.S. Supreme Court rulings on abortion and affirmative action, would have softened support for Bannon’s analysis (or at least served as a reminder of the importance of state power in domestic affairs). And yet the irony is that, just as conservatives are reaping the fruits of their politics-over-culture strategy, they are rushing to abandon it. One can see this in the tidal wave of illiberalism emanating from Florida, which is best understood as an attempt to leverage control of the political system into influence over culture. In so doing, conservatives are fighting for a prize that’s not worth winning. American progressives overplayed their hand so dramatically, generating such intense cynicism and backlash, that there is barely any need for conservatives to prosecute their side of the culture war.

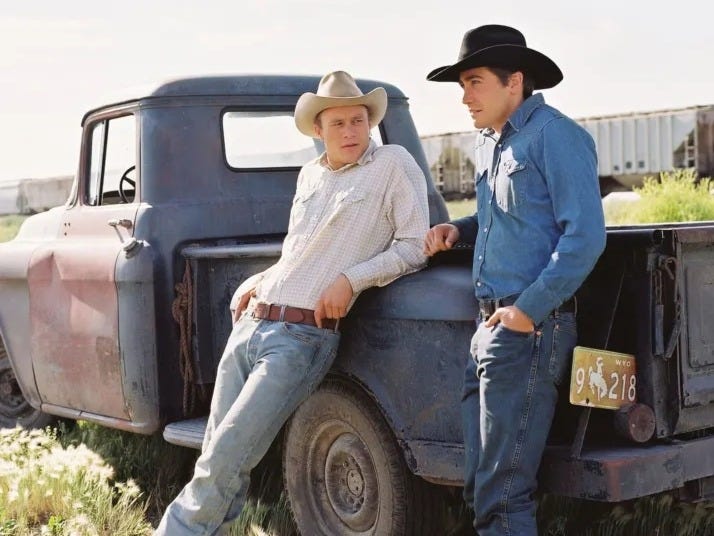

My argument on this is a bit complicated, so it will be helpful to start at the beginning, trying to understand how conservatives came to believe that their willingness to cede Hollywood to the liberals was a mistake. Here the major event was the sea-change in public opinion that occurred with respect to homosexuality, which coincided with the legalization of same-sex marriage in the first decade of this century (for a summary of trends in public opinion, see here). To understand how conservatives misread this episode, it is helpful to revisit the surprising success of the movie Brokeback Mountain, which came out at the same time that the shift in public opinion was reaching critical mass. Or more specifically, it is important to understand how conservatives misinterpreted the success of this film, which in turn caused them to vastly overestimate the strategic value of controlling Hollywood.

Where did conservatives get the wrong idea from?

Looking back over the big debates that occurred in the early 21st century on the subject of same-sex marriage, I guess the thing that surprises me most was that conservatives didn’t expect to lose this fight. They genuinely believed that because a majority of Americans (prior to 2006) thought homosexuality was a sin, they would be able to continue to block any legal recognition of same-sex relations.

My natural inclination was to see the whole debate through a John Stuart Mill lens, as a question about the social regulation of what amounted to private behaviour. It seemed obvious to me at the time that the day after gay marriage was legalized, the whole conflict would disappear, because while the question of who can marry who is a big deal for those who are directly involved, it doesn’t really affect anyone else in any appreciable way. There were some quibbles about whether legalization should take the form of civil union or gay marriage, but it seemed clear that if governments acted decisively to establish legal equality among partnerships, opponents would find it practically impossible to mobilize for a reversal, because there would be no constituency that stood to gain from it. The whole issue could easily be portrayed as a conflict between a bunch of (largely Christian) busybodies, who wanted to tell other people how to live their lives, and gay/lesbian people, who were asking to be left alone.

On this reading, the struggle for marriage equality was just one in a series of liberalizing reforms, in which the state became more willing to let people run their own lives without second-guessing their judgment. The decriminalization of homosexual relations, one may recall, happened during a time that a large majority of the population continued to disapprove of it. In Canada, it was part of a series of reforms that also involved the decriminalization of contraception and “indecent” acts between heterosexual couples. The logic of these reforms was summed up well by then-Minister of Justice Pierre Trudeau’s declaration that “government has no business in the bedrooms of the nation.”

So if one were to look at the arc of history, it seemed inevitable that gays and lesbians were going to win the marriage equality fight. Many U.S. conservatives, however, appear to have been blindsided by this, and so began shopping around for explanations. In a classic case of mistaking a symptom for the cause, they decided that growing public acceptance, encouraged by cultural productions such as the TV show Will & Grace, or the movie Brokeback Mountain, explained the sudden shift in public opinion. According to this analysis, Hollywood liberals had essentially “normalized” same-sex relations, by portraying them in a positive light, thereby undermining support for the traditional family.

This is a terrible misreading of Brokeback Mountain. It’s actually interesting to rewatch the movie now, at a time when Hollywood is struggling to convey a liberal message without provoking backlash or ridicule. The first thing to observe about Brokeback is that the director, Ang Lee, is not gay, and many gay men disliked the film when it came out, in part because it catered to a heterosexual sensibility (i.e. that of its primary audience) in various ways. The second thing to note about the film is that it quite explicitly tied the struggle against homophobia to a set of universal themes. (In some ways, the movie is just another version of Lee’s Eat Drink Man Woman: “watch and sympathize as unreasonably good-looking people find their lives being destroyed by outdated social conventions.”)

More important, however, is the central message of the film. What the two main characters needed, more than anything else in the world, was to be left alone. Their lives were ruined because they lacked the freedom to live the way they wanted. Indeed, what annoyed many conservatives about the film at the time was the way that Lee used the wilderness and mountain landscapes as a symbol of freedom, but gave it a twist by using them to represent freedom from the constraints of society and social convention.

The central political demand made by the film was absolutely unambiguous: leave us alone. This is a message that Americans are both temperamentally and constitutionally predisposed to accept. The film was not an example of Hollywood brainwashing Americans into thinking that it’s cool to be a gay cowboy. It was Hollywood repositioning the struggle for marriage equality as part of a larger narrative of expanded individual freedom that has been central to American values for centuries. It was also not an example of politics being downstream from culture, but rather the opposite. The values that informed Brokeback Mountain had already achieved legal recognition in the decriminalization victories of the late 1960s and ‘70s. It took another two decades before the culture began to shift, and another decade before general public acceptance was achieved.

The rise of Netflix casting

One of the charming things about Americans is that they’re only good at making propaganda when they don’t realize they’re making propaganda. As soon as they try to do it intentionally, they suck. As a result, Hollywood studios used to be really good at promoting liberal values, but once they became convinced that this was their special calling, they started to become much worse at it.

The most striking change, during my lifetime, has been the rise of virtue signalling in American cultural products. It’s as though subtlety acquired some sort of moral stigma. I can’t claim to understand why this is – some of it may be just internal politics within media corporations. Nevertheless, it is apparently no longer sufficient to advance progressive values, one must also draw attention to the fact that one is advancing progressive values. This is most obvious in casting choices, where the effort to find a plausible rationale for introducing greater diversity has in many cases been replaced by the opposite desire, to introduce diversity where it makes no sense. The latter, presumably, constitutes a stronger signal of commitment – it shows that one is doing it, not because the story calls for it, but rather despite what the story calls for.

The problem with all of this virtue signalling in cultural products is that virtue signalling is, almost by definition, immersion-breaking. While it does not technically “break the fourth wall,” it has the same effect. Not only does it draw attention to the artificiality of the product, it does so in a way that references the audience. And yet when people complain about this, the standard response has been to tell them that they are foolish for having become immersed in the first place – after all, isn’t the whole thing obviously fake? In so doing, the creators of these cultural products are simply forfeiting the most powerful weapon in the arsenal of artistic techniques, which is precisely the ability to captivate an audience.

Similarly, the attempt to move from gay and lesbian rights to trans acceptance has become something of a trainwreck, demonstrating along the way the inherent limitations of the culture industries. In part this is due to a failure to think politically about the issues involved, and to recognize that the “ask” involved in trans acceptance differs radically from the older LGB demands. While the “leave us alone” demands enjoy considerable public support, a large number of trans activists have been making the much more intrusive demand that the entire population reconceptualize their gender identity – such that men and women who are accustomed to thinking of themselves as simply men and women must now begin to think of themselves, and in some cases introduce themselves, as cisgendered men and women. Similarly, the new politics of pronouns attempts to give a small segment of the population the power to unilaterally turn every conversation into a Stroop task, in a way that again affects the entire population.

Astonishingly, many people seem to have believed that these objectives could be achieved without engaging in any of the traditional give-and-take of public debate or political contestation. In particular, the expectation seems to have been that it would be unnecessary to present arguments in support of these demands, or to respond to common objections. This strongly suggests that, somebody, somewhere, vastly overestimated the strength of their position. It may take a long time to figure out exactly how a small, unpopular minority could have persuaded itself that intolerance could be a useful weapon in its political arsenal. But part of the answer, I suspect, involves their early success in achieving outsized influence within certain elite institutions, including media corporations, and then vastly (vastly!) overestimating the effectiveness of these cultural institutions at achieving social change. Treating culture as a system of mind control, and believing that the culture industries have the power to program culture, no doubt contributed to this overestimation. Although this was the Frankfurt School thesis, there has been ample evidence for some time that it is incorrect. In reality, what the increasingly self-conscious liberal control of Hollywood has achieved is nothing but growing tide of ridicule, alienation, and backlash.