My two cents on Abundance

Like everybody and their dog, I have written a review of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s Abundance book and Marc Dunkelman’s Why Nothing Works. I did it for the journal Commonwealth and Comparative Politics, where it is unlikely to see print anytime soon, and so I posted an advance copy to my academia site (here). As I mentioned in the review, the reaction to these books was in some ways more interesting than the books themselves, so I thought I might take an opportunity to elaborate on this claim, since these observations don’t really belong in an academic journal review. I thought Dunkelman’s book was better, but I’m going to talk about Abundance because it’s the one that has generated more debate.

Surveying the complaints that have been lodged against Abundance (the abundance agenda, abundantism, etc.) it struck me immediately that there was a problem with the political positioning of the book. Many critics reacted to abundance as though it were offering an alternative to the pursuit of a more overtly left-wing agenda (focused on an extension of the welfare state and more aggressive redistribution of wealth). A better way to think about it would be to see the abundance agenda as an attempt to create the preconditions for advancing the more assertive left-wing agenda. A major impediment to the expansion of the welfare state in America is the fact that public administration in that country is really, really bad. Before you can give the state new tasks to perform, you need to create a state apparatus that is actually capable of carrying out those tasks.

Unfortunately, trying to convince Americans of this can be incredibly frustrating. It reminds me a bit of the big debate that erupted in Canada 15 years ago over public sector corruption in the province of Quebec. The dominant reaction, in the province, was one of defensive denial: “there is no corruption, this is just Quebec-bashing.” Once it was established, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that there was a serious problem of corruption in Quebec, those same people switched to saying “okay, maybe there is some corruption, but it’s just as bad in all the other provinces.” It is, of course, difficult to prove a negative, and so that left most of us with only the pleading response: “trust me, it isn’t that bad in other provinces…” But of course, since most Quebecers have never lived outside Quebec, they have no way of seeing what is self-evident to other Canadians.

Trying to talk to U.S. Democrats, much less Democratic Socialists, has roughly the same dynamic. One starts out by suggesting that perhaps Americans are anti-government because the U.S. public sector is horrendous to deal with – at every level, federal, state and municipal. This is often met by straightforward denial. One then points out the various ways in which simple tasks inevitably involve byzantine paperwork, enormous queues, 1980s technology, the impossibility of speaking to a person, and a ubiquitous threat of punishment for even the slightest error. This elicits the fallback position, which is that “all governments are like this.” To which one can offer only the pleading response: “no, seriously, all governments are not this bad.” But again, since most Americans have never lived outside America, they have no experience of even quasi-efficient public administration, and so no way of seeing what is self-evident to non-Americans.

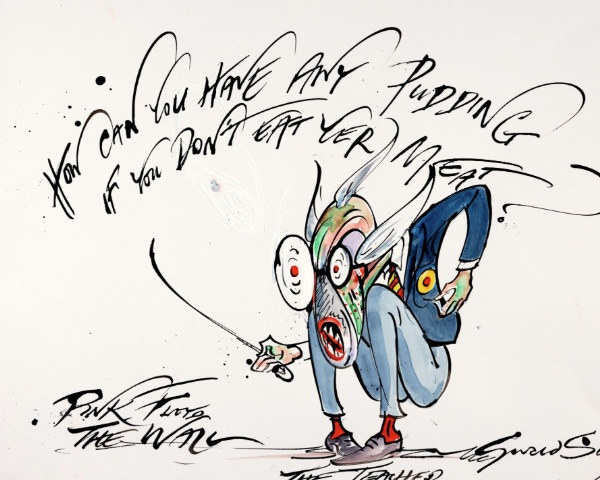

So if I could inject just one observation into the great American Abundance debate it would be this: what these abundantists are saying, about making U.S. government work better, especially in places like New York and California, is absolutely self-evident to non-Americans. The fundamental problem with the left in America is not that their aspirations are misguided but that they want to eat their pudding before finishing their meat.

Or, to translate this into American idiom, they want to go straight to dessert without eating their vegetables. American progressives want a Swedish-style welfare state without doing any of the hard work that is involved in creating a state apparatus capable of delivering a Swedish welfare state. There are thousands of examples of this, but one that I found particularly striking was Elizabeth Warren’s call for the introduction of a wealth tax. This is a typical “all-pudding no-meat” position. There are various objections to wealth taxes, but one of the most significant is that imposing them requires the creation of an entirely new administrative system, since taxpayers are currently only required to report their income to the government, not their wealth. You can’t just add a few extra lines to the income tax form. The problem is that in 2020, when Warren was campaigning on this, the U.S. federal government barely had the capacity to collect an income tax.

This is something that I discovered for myself, unfortunately, when I ran into a little problem with the U.S. IRS. For biographical reasons that are not important to the story, I have both an SSN and an ITIN. I filed some U.S. tax returns under my ITIN, which required some adjustments, resulting in a letter from the IRS saying that I owed them money. I paid the amount owing online, using the IRS’s new system. I thought everything would be fine, but there turned out to be a worm in the apple. The payment that I made online got registered under my SSN, not my ITIN. As a result, I kept getting letters from the IRS saying that I owed them money.

This was the beginning of a saga that took – I kid you not – over 18 months to resolve. I started out thinking I could sort things out by mail, and so I sent in paper copies of the receipts, showing that the balance had been paid. That generated no response, so I had my accountant send a more formal version of the same. Again no response. Meanwhile, I started receiving more threatening letters from the IRS, informing me that unspecified penalties had been added to my account, so that I would now have to call the IRS and speak to an agent, in order to find out the amount owing (or they would seize my assets, garnish my wages, etc.)

So far this was all just run-of-the-mill IRS hassle. Things took a turn for the weird, however, when I tried calling the IRS. After navigating through a bit of voicemail, I received a recorded message saying that there were no agents available to speak to, at which point the system hung up on me. Meanwhile, I kept receiving letters, telling me that I had to call and speak to an agent, or dire consequences would follow. I cannot recall this having happened to me ever before, with any government agency – simply being hung up on.

It turns out my experience with the IRS was hardly unique. Here is the 2022 Government Accountability Office report on IRS customer service:

During the 2022 filing season, CSRs [Customer Service Representatives] answered fewer calls than during the prior year, even though call demand was lower. Specifically, CSRs answered about 58 percent (6.3 million) fewer calls during the 2022 filing season compared to the 2021 filing season, despite a 67 percent (131.3 million) decrease in call demand. Further, about 43.1 million incoming calls did not reach IRS—26.2 million calls that IRS disconnected due to lack of CSR availability, 16.6 million calls that the taxpayer abandoned, and nearly 310,000 calls that received a busy signal.

Just to highlight the important bit: the IRS answered only 6.3 million calls, compared to 26.2 million that they hung up on.

I asked my U.S. accountant what to do; they suggested getting up early and calling as soon as the IRS office opened (“that’s what we do”). I followed this advice, and after a few weeks of trying off and on actually got through to a person. The agent was able to confirm that the problem was being caused by the system thinking that I was two different people (this was about 12 months into the saga). The solution, she said, was to merge the two files, but after some time on hold and consultation with a manager, announced that she was unable to do it. Instead, she gave me the address of a different IRS office than the one I had been writing to, and instructed me to write them a letter, explain the problem, and send them my receipts. I did this, then waited several more months. (Every 60 days that passed, I would receive a letter from the new office, saying “thank you for your correspondence, we are still working on it.” Meanwhile, I was still getting the threatening letters from the old office.). Finally I received a letter informing me that the files had been merged (along with no information about what had been done with the unspecified “penalties”).

I don’t want to bore everyone with the details of all this, I’m just telling the story because it was so mind-blowing to me. Like most Canadians, I’ve had my frustrations with the Canada Revenue Agency, but nothing that even vaguely resembled this. The low point undoubtedly was the moment on the phone with the IRS agent, when she told me that she was looking at the computer, and could see what the problem was, but that she couldn’t fix it, but also that she couldn’t escalate the request to have it fixed. It was, quite simply, pathetic.

The larger point is that the IRS is barely capable of administering an income tax. The idea that they could administer a wealth tax is like something out of science fiction. (Almost as crazy as thinking that the City of New York could run a grocery store!) The problem is that when Americans encounter this sort of incompetence in the public sector, they take it to be an indictment of government in general, not American government specifically. (My friend Christopher Morris once waggishly suggested that there should be a position in political philosophy called “American libertarianism,” which differs from general libertarianism in that it has no objection to government performing various economic functions, it just doesn’t want the American government to perform them.)

Of course, the Biden administration was trying to fix the IRS, and indeed was making some progress, until everything they were doing was destroyed by the new Trump administration. Unfortunately, there is no way to avoid these meat-and-potatoes problems. Part of the reason Americans are hysterically opposed to taxes is that the U.S. income tax system is horrendously complicated, completely non-transparent, imposes massive administrative burdens, and is collected by an agency that is both menacing and incompetent. This is a massive problem for the left in America. But when people come along and say “our top priority should be to fix the IRS, before we try to impose new taxes,” they get called centrist sell-outs.

Let me give just one more example of this, to make it clear that the issue is not just taxes. There are currently over 18,000 distinct police forces in America (as compared to about 160 in Canada, 48 in the U.K.). It is quite literally impossible to resolve many of the difficult problems in policing in America without consolidating most of these polices forces in a small number of large organizations (which could, in turn, be subject to professional management). So the first step to improving policing in the U.S. would be to absorb pretty much every local county police force or sheriff’s office into the state police force. This is the meat-and-potatoes of police reform. It is a precondition for being able to advance many of the issues on the social justice checklist. And yet U.S. progressives don’t want to hear about this sort of thing, they want to jump straight to the pudding. They want social justice, without having put in place any of the institutional preconditions for the attainment of social justice.

How can this tendency be corrected? Allow me to end with another suggestion drawn from Quebec politics. After losing the referendum on independence in 1995, Quebec separatists realized that much of the desire to remain in Canada was driven by economic insecurity. The fact that Quebec had the highest taxes in Canada, and yet still relied on massive fiscal transfers from the rest of the country to finance public services, was not really helping the case for Quebec independence. So the separatist party decided that, rather than campaigning on a promise to hold another referendum, they would prioritize instead the creation of “winning conditions” for that referendum. The idea was that they would focus on improving the economy, reducing the government deficit, improving the quality of public services (and, incidentally, improving relations with First Nations), in order to create the confidence among Quebecers that secession would further improve their lives.

This was, in certain respects, the best thing that ever happened in Quebec politics. “Winning conditions” became a mantra among sovereigntists, essentially giving them an excuse to focus on fixing all the day-to-day bullshit that Quebecers have to deal with, but to do it under the guise of advancing a more radical nationalist project. This is the sort of thing that Americans need right now. The abundantist agenda is basically about eliminating some of the bullshit that has accrued over time in U.S. government regulation – especially in the area of infrastructure and housing construction. U.S. progressives should not be thinking of this as a capitulation to neoliberalism, but rather as a way to create “winning conditions” for their more heartfelt aspirations.