Why philosophers should worry about cancel culture

Over the past few years I have been surprised and disappointed by the number of my colleagues in philosophy who have been willing to jump on various online bandwagons, attempting to punish or intimidate members of the profession for speaking their minds on different subjects. At the risk of sounding a bit supercilious, I must admit to finding this sort of behaviour particularly surprising coming from philosophers. When I first read Plato’s dialogues recounting the trial and death of Socrates, my natural inclination was to side with Socrates, not the Athenian dicasts. I just assumed that most professional philosophers felt the same way, or had similar formative experiences. I was surprised therefore to find so many of them eager to imitate the dicasts, rather than the philosopher persecuted for speaking his mind (or, in the more recent cases, her mind).

A lot of this seems to be based on the belief that, so long as you’re not calling for someone to be fired, but just trying to ruin their day, it’s okay to jump onto an online dogpile. This is typically bolstered by a sense of personal immunity derived from having political views that accord perfectly with the prevailing left-wing consensus in the university. After all, it’s only the nail that sticks out that gets hammered. If you don’t hold incorrect political views, then you shouldn’t have any reason to worry about cancel culture (and, of course, if you do hold incorrect political views, then the problem lies in the incorrectness of those views, not the excesses of cancel culture). In my previous post, I suggested that this political way of understanding cancel culture is mistaken. Cancel culture arises from a change in the structure and dynamics of public discourse. As a result, there is no substantive position one can take that will offer immunity from its effects.

In order to emphasize this point, I would like to draw attention to certain disciplinary practices that are currently widespread in philosophy that are threatened by these structural changes. My impression so far is that philosophy departments have remained something of an oasis of non-dogmatism in a growing sea of ideological conformity. (Many of my colleagues, I should note, seem to be asleep at the switch on this point. The idea that an instructor should present the arguments both for and against every position is so deeply embedded in our pedagogical practices that many philosophers appear not to realize, or have difficulty believing, just how dogmatic things have gotten out there.) So in order to bring things home, I would like to describe certain norms that prevail in the discipline of philosophy that are threatened by the new communication environment.

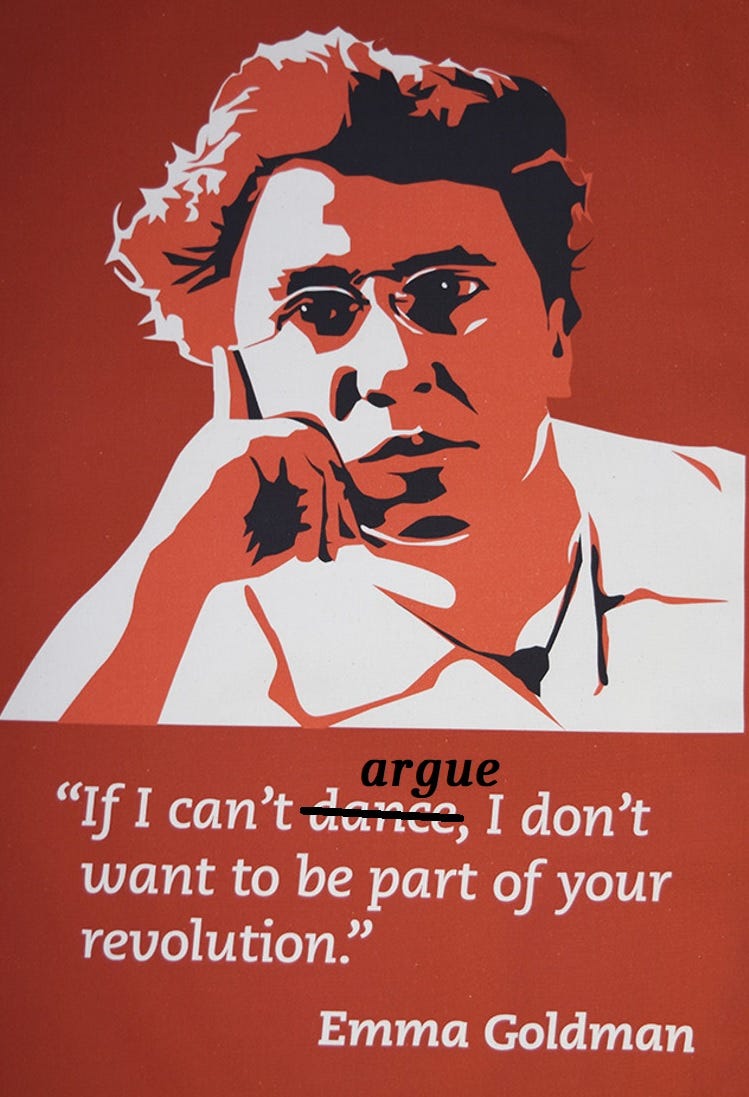

Some of this is so obvious that even the most politically correct among my colleagues agree that things have gone too far. For example, pretty much everyone recognizes that philosophy institutionalizes a very high level of tolerance for what the kids call JAQ-ing off (“just asking questions”). The attempt to rule this out in online culture is therefore a straightforward threat to the discipline. Questions like “how can you be both a vegan and pro-choice?” may seem like trolling in an online space, but in philosophy it’s a perfectly reasonable thing to ask. Similarly, the attempt to classify the impulse to argue with any of the claims made in a DEI presentation as a symptom of “white fragility” is a bridge too far for most philosophers. The right to argue is so much a part of the DNA of the discipline that when people come along trying to prohibit, pathologize, or punish the behaviour, most philosophers recognize it as a threat to their livelihood.

There are however some more subtle challenges arising from the phenomenon of context collapse. Philosophers are highly vulnerable to having speech that is perfectly unexceptionable according to the internal norms of the discipline become the subject of hostile reaction when transmitted to outside audiences. I can think of at least three norms that prevail within the discipline that are not respected in public discourse, and that expose philosophers to cancellation risk:

1. Affective neutrality in discussion of moral and political issues. One of the major differences between philosophers and the general public is that most people find it extremely difficult to discuss any controversial moral or political issue without getting upset. Philosophers, on the other hand, typically draw a distinction between entertaining a proposition and affirming it, and so assume that one should be able to debate various questions in a hypothetical register, without triggering any of the emotional reactions that might be appropriate if one actually held them. As a result, there is a disciplinary tradition in philosophy of maintaining a stance of affective neutrality when discussing morally charged issues, and even when contemplating abhorrent conclusions. (Instructors sometimes forget this when teaching introductory moral or political philosophy, and so launch into a whimsical presentation of various horrible scenarios, thereby alienating many students, who infer from the emotional tone of the discussion that the instructor does not actually care about the issues.)

To pick one out of thousands of examples, consider the casual way that Robert Nozick introduces what became a well-known scenario:

If someone picks up a third party and throws him at you down at the bottom of a deep well, the third party is innocent and a threat; had he chosen to launch himself at you in that trajectory he would be an aggressor. Even though the falling person would survive his fall onto you, may you use your ray gun to disintegrate the falling body before it crushes and kills you? (1974, 34)

This example has generated an enormous philosophical literature, despite the fact that it is rather gruesome (indeed, some of that literature involves adding even more whimsical variations to it – e.g. “suppose you could shoot off just his legs, so that you would only be maimed by the impact…”) Most philosophers who read the passage, however, being familiar with the genre, simply gloss over the violent aspects and focus on the point Nozick is trying to make, which concerns the permissibility of using lethal violence in self-defence against someone who is not intending to harm you. It is because the case is non-standard that he has to make up a somewhat fanciful scenario. But the goal is also to elicit a cognitive judgment not an emotional reaction.

This vignette-based approach to moral philosophy is not actually timeless and eternal, but developed rather in the context of post-war Oxford analytic philosophy. It originally offended continental Europeans as well (mainly on the grounds that it conveyed a lack of moral seriousness). Since then, however, it has more-or-less conquered the world, despite having its critics. Increased susceptibility among students to being “triggered” by the use of certain words has led to the development of slightly greater caution among instructors about the use of gratuitously upsetting examples. Nevertheless, the point about affective neutrality remains an important one. While we could probably do without all the whimsical examples, it is difficult to see how we can do our jobs without being able to debate contentious issues in an emotionally neutral manner.

Consider this example of Chandran Kukathas presenting his view that genocide is not that bad. There are no whimsical examples here; the tone is one of strict moral seriousness. At the same time, it is also one of total affective neutrality, on both sides of the discussion (e.g. “I wonder if you could give us some examples of genocide that fall under your description?”). If you were to ask me, I would say Kukathas is a model of perfection throughout according to the norms of academic philosophy. At the same time, the position he is defending is one that is pretty radioactive in Canadian public discourse, and could easily get you cancelled if expressed in a public forum. Why? Because people get upset when talking about genocide, and so setting up your position carefully, as Kukathas does, clearly specifying what he is and is not claiming, doesn’t count for very much. (Just to be clear, I was caricaturing his position in the first sentence of this paragraph. What he is doing is questioning whether genocide constitutes a distinct harm above and beyond the killing.)

Over time, a lot of people working in philosophy start to take this sort of affective neutrality for granted – to the point where the Kukathas interview seems to them perfectly unremarkable. This leads them to forget just how far offside a lot of the views that we debate are with the general public. Anyone who teaches John Stuart Mill on freedom of expression, for example, should have been spooked by the cancellation of Tom Flanagan for expressing a fairly mainstream academic view on child pornography. The standard argument for the legal prohibition of child pornography is based on the harms involved in its production. As Flanagan observed, this rationale fails to justify the prohibition of artistic representations, the production of which involves no harm to any actual child. This issue is one that obviously must be open to debate, now more than ever. (What are we to say about a person who uses AI image generation to produce ephemeral child pornography for personal consumption, retaining none of the images?) And yet it’s difficult to discuss these issues under the threat of a 60-second clip being recorded and uploaded to YouTube.

2. Reconstructive presentation of arguments. Since the good old days of ancient Athens, philosophers have taken themselves to be more interested in argument than in rhetoric. This is reflected in a variety of disciplinary practices, including the sometimes elaborate efforts undertaken to avoid scoring merely symbolic victory over “straw man” versions of one’s opponent’s position. One of the most basic components of a philosophical education therefore involves learning how to demonstrate, prior to criticizing a position, that one has a correct understanding of it, and that the view is worthy of being taken seriously. This is why we make undergraduates in all their papers go through the lengthy process of explaining various arguments before presenting their evaluation. This does not come naturally to most students – most people are far too eager to jump in with their objections. The idea that you should hold off on one’s criticism, presenting the view that one disagrees with in a complete and sympathetic manner, requires a great deal of self-discipline, which typically takes years to cultivate.

Because of this, it is extremely common for philosophers to spend a fair bit of time offering “reconstructions” of positions that they do not actually hold. Indeed, it is not unusual for the first half of a research talk or conference presentation to consist of such reconstruction. Many of us have developed some enthusiasm for the practice – since the type of positions worth engaging with are typically not unreasoned, once one catches the thread of the argument it is difficult not follow it along, which often makes one sound like one is endorsing it. It is possible to admire the inner coherence of a position and to communicate that to an audience without at the end of the day endorsing it. This generates certain risks, however, that with context collapse, along with the shortened attention spans of online audiences (or uncharitable video editing), one will to be taken to have endorsed a position that one does not actually hold. This is precisely what generated the deplatforming of Daniel Weinstock – a truncated segment of his remarks at a conference, in which he was merely describing a position in a broader debate, was used to ascribe to him a position that he did not actually hold. Surely this is something that could happen to anyone in the profession! (Also, the fact that Daniel successfully fought back does not mean that the experience was not profoundly distressing.)

3. Stipulative definition of terminology. Because of the somewhat obsessive interest in argument that is central to the profession, philosophy also places a great deal of emphasis on the definition of terms. In order to track inferences it is essential to be clear about what one is and is not committed to in making a particular claim, and in order to be clear about that one must be clear about the terms one is using. This demand for terminological clarity generates both obligations and entitlements. We tend to be more aware of the obligations – there is little tolerance of ambiguity and equivocation, and so philosophers are always under pressure to provide definitions of their key terms. But there is also an important entitlement, which is that philosophy gives its practitioners broad license to engage in stipulative definitions of terms. So if one says that “X =def Y” then for the purposes of the argument that follows, X means Y, and one can only be held accountable for the inferences that follow from that. In particular, the fact that other people use X to mean Z becomes irrelevant to the argument.

Again, philosophers have become so used to this disciplinary practice that they often take it for granted. Yet it is also quite unnatural. Indeed, one of the most common flaws in undergraduate papers occurs when dealing with writers who employ vocabulary in highly regimented or non-standard way (e.g. defining “desire” as “a propositional attitude with world-to-word direction of fit”). Students will sometimes quote the definition, but then fail to sustain it, and so revert to the ordinary-language sense of the term a few pages later. Being able to accept a strange definition of a term, and then track the consequences of this across complex set of inferences, involves a demanding form of “cognitive decoupling” that takes years to cultivate.

I never thought of this as a special skill of philosophers until a few years back, at the annual Canadian Philosophical Association conference, when I did an author-meets-critics session on Paul Bloom’s book Against Empathy. I was first to present, and so I started by saying something along the lines of “before you get all worked up, you should be aware that Paul is using the term ‘empathy’ in a very particular sense.” I then went on to present his definition, followed by some critical remarks, and the rest of the discussion proceeded without misunderstanding. Afterwards, however, Paul (who is a psychologist) mentioned to me how strange he found the entire session. What he found most unusual was that the entire audience simple accepted his (somewhat unintuitive) definition, and proceeded to discuss the claims on that basis. In psychology, he said, audiences would spend the entire session challenging the definition, arguing that, in effect, he had a mistaken understanding of empathy. He found it pleasant but also strange to encounter an entire roomful of people who were prepared to grant him his definition, without a fuss, in order to focus their attention on what followed from it.

Needless to say, this indulgence that philosophers are willing to show one another, when it comes to the use of terms, is not shared by the broader public. Most obviously, speakers who have been targeted for cancellation have been strikingly unsuccessful in attempting to defend themselves through clarification of their semantic intentions. Context collapse has been something of a field day for those who are keen to engage in uncharitable interpretations of the speech of others, but attempts to clarify one’s meaning through reference to the context of utterance have usually failed to placate online mobs. The official doctrine is that the harms of speech should be determined by the actual effect it has on others, not the effects intended by the speaker. More specifically though, proponents of cancellation have often rejected the sense/force distinction, and so have sought to penalize speakers for using words that have negative associations. This seems to have played a role in the cancellation of Jonathan Anomaly, where his definition of the term “eugenics” (in an academic journal article) was ignored on the grounds that the word has “negative historical associations.” Again, this is something that should be of concern to all philosophers (including those who are not inclined to sympathize with Jonathan). It suggests that being careful and fully explicit in the specification of one’s claims may not be adequate protection against attacks based on uncharitable interpretation.

In conclusion: it is important to emphasize that I am describing disciplinary norms here. There are people who violate and abuse these norms, so I am not claiming that one can justify any sort of behaviour through appeal to them. The examples I have pointed to are ones in which academics have been targeted for cancellation because of behaviour that does not violate prevailing disciplinary norms. Of course, one could argue that things need to be tightened up a bit within the discipline, and that we need to be a bit less generous in how provocative we allow the presentation of arguments to become. My concern is rather that the norms themselves are under threat, and that context collapse will make it increasingly difficult to preserve the type of discursive spaces that have allowed philosophical inquiry to flourish in the past century.