Decline, what decline?

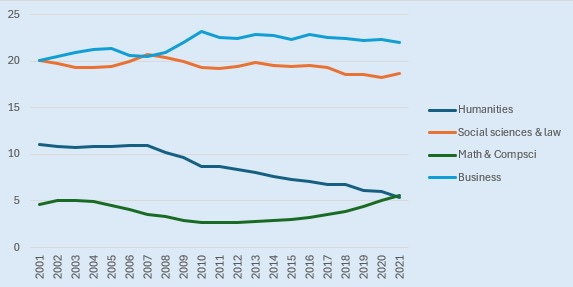

There has been a great deal of handwringing in recent years over the trend of declining enrollments in the humanities. Most of the discussion has focused on U.S. universities, with commentators assuming that whatever is happening in the U.S. must be happening in Canada as well. In this case, however, it happens to be true (although I am not certain that it is happening for the same reasons in Canada as in the U.S.). Here is what Statscan shows, when you pull up the data on university subject graduation rates from 2001-2021, and look at different majors as a percentage of the total:

An important point to observe is that the number of students graduating has approximately doubled over the past two decades (from 178,215 to 351,513), so the disciplines with constant enrollment shares shown here (social sciences/law and business/commerce/management) have approximately doubled the number of students they are graduating. Humanities departments, by contrast, have been graduating the same number of students, and so their share of the total has been declining. The long-term trend is pretty unmistakable. (I threw in computer science as well, to show what most of us have been seeing from the inside, which is that they had a big bump during the dotcom era, followed by a very long period of flat enrollments, followed by a major boom in the past few years.)

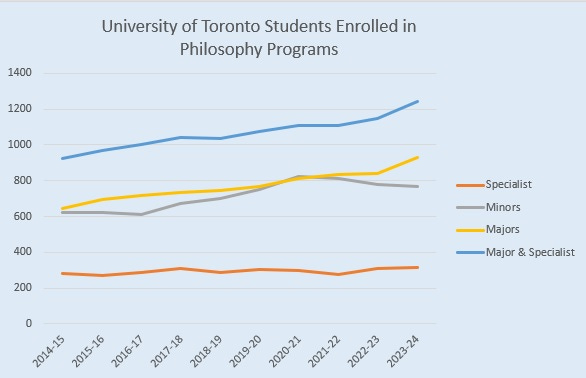

Given these overall trends, many of us have been surprised by the numbers we’re seeing in our own department. The next graph shows the number of program enrollments for the downtown campus, Department of Philosophy at the University of Toronto (and therefore does not include the two suburban campuses, in Scarborough and Mississauga). People sometimes have difficulty believing these numbers, because they don’t realize quite how big the University of Toronto is. With over 97,000 students, 76,000 of them undergraduates, we are a pretty serious operation. (I haven’t checked recently, but I would imagine that our philosophy department is still the largest in the English-speaking world.)

As one can see from this, we currently have just over 1,200 students enrolled in our program. That includes philosophy majors and those enrolled in our more intensive “specialist” program (elsewhere often referred to as an “honours” program). I am ignoring students who are taking minors, because a minor can be combined with any other sort of degree, and so doesn’t tell you much about what students are doing. (Nevertheless, you can see a clear movement away from minors toward majors in the past few years). The Mississauga campus has about 500, and Scarborough another 200, so all together we have close to 2,000 students doing philosophy as their primary degree. (Students usually declare their major in second year, so divide that number by three to know approximately how many we are graduating per year.)

These are pretty big numbers. I suspect that if you added it all up, we are educating more students in philosophy than the entire U.S. ivy league combined. As far as our ranking is concerned, the quality of the department puts us in the middle to upper end of the ivy league. Furthermore, unlike places like Harvard and Yale, where grading practices have become something of a joke, we maintain rigorous standards in our courses. It is still very common for our large introductory classes to finish with course average of C+, and it is uncommon for more than 20% of the class to receive grades in the A range. In other words, students are not coming to our program because we make them feel good about themselves.

So what’s behind all this? In my previous post on cancel culture, I mentioned that philosophy departments have remained something of an “oasis of non-dogmatism” in the current university environment. I would like to believe that this is playing a role in our enrollments, but I genuinely do not know. Rather than just theorize about it (as the philosopher in me is inclined to do), we have undertaken to conduct a study to find out (basically, we’re going to ask our students). I looked forward to reporting the results when they become available.

In terms of institutional context, I should mention that the most important trend affecting enrollments at Canadian universities is the increase in the number of international students. Overall enrollment in the Faculty of Arts and Science has been essentially flat during the past decade (and so the increase in program enrollments shown above is not “beta” growth, but rather “alpha”). What has changed is the proportion of foreign students. Most importantly, the university has more than 15,000 students from the People’s Republic of China. That has been tough on some humanities departments, and good for departments where English-language skills are less important.

Philosophy, however, is a language-intensive discipline, which has traditionally had fairly significant entry barriers for ELL (“English as a Learned Language”) students. So what gives? I don’t have any data on this, but two things I’ve observed in my own classes: First, many Chinese students are really, really interested in Western philosophy, especially Western political philosophy. Second, Chat-GPT-derived grammatical aids have reduced some of the unfair advantage suffered by ELL students, making humanities courses more accessible. Furthermore, greater reliance on exams, rather than papers, helps foreign students, who typically have better exam-writing skills than Canadian students. It will be interesting to see how this plays out over the next decade.

As far as the overall decline in the humanities is concerned, I’m not quite sure what advice to give. Certainly all of the whining about how students have become preoccupied with their future earnings prospects, or how “neoliberal” reforms have been sweeping the university, are not particularly constructive. That stuff has been happening at the University of Toronto, and yet somehow we’ve managed to persuade two thousand students to do degrees in philosophy. If anything, I would encourage people to worry less about the game being rigged and to focus more on the product being offered.